Michèle Faguet: Helena Producciones is best known for organizing the Festival de Performance de Cali, but since 2007 you have also engaged in an equally significant parallel project known as the Escuela Movíl de Saberes y Práctica Social: a series of workshops and community-based projects that takes place in Colombia’s Pacific region and is funded by the cultural ministry. Could you tell me about the Escuela?

Helena Producciones: As the name indicates, the Escuela attempts to examine and broaden the methods of teaching art that was introduced and put into practice in Colombia beginning in 2000 when the cultural ministry began to offer grants that promoted the format of workshops. Informed by the tradition of deschooling, the Escuela emerged from a desire to enact dialogues between different groups of people, and to negotiate and reconstruct local history through documents, practices, material resources, memories, and so on. The dynamic of this school is completely open. We organize conversations around four themes, including personal narrative, the family, the natural environment, and material culture/collective history. Participants then define their own interests and are given the opportunity to modify or broaden these themes or to propose entirely new ones. The school has been implemented in diverse environments, including many rural areas of Colombia where certain historical and political discourses have been suppressed. One of these places was the Pacific Coast, but we have also enacted the school in the departments of Cauca and Nariño and in the city of Popayán. The school has also occasionally traveled outside of Colombia—for example, to San Francisco, California.

Much of the funding of the Escuela has come from the Colombian cultural ministry in the form of project grants. We have utilized public money because we feel we are entitled to it, especially because we do not come from the upper class as do so many other artists in Colombia.

arrow_upward

arrow_upward

arrow_upward

arrow_upward

arrow_upward

arrow_upward

MF: How was it initiated and how does it relate to other aspects of Helena’s practice?

HP: Once we decided to continue producing the festival on a regular basis (following the inaugural edition), we became interested in supplementing the one-day marathon performance session with a series of talks about performance and related themes, and over time this led us to rather intuitively explore a temporal and mobile system to encourage dialogues among other populations of the city and region.

In 2005 we were chosen to curate the 11 Salón Regional de Artistas, zona Pacífico, and rather than select works from the archives of images on our computer, we chose to apply the research methodologies that eventually resulted in the formation of the Escuela. We visited many different towns, where we asked the people there how they defined art and the artist, so that the resulting exhibition reflects a clear relationship between local modes of cultural production and art. In this sense the curatorial methodology also engaged with the process of deschooling society proposed by Ivan Illich. That same year we also proposed a project for a new program sponsored by the cultural ministry called Laboratorios de investigación creacion. While exploring the relationship between education and art we conceived a unique format to articulate our ideas that we called the Escuela Móvil de Saberes y Práctica Social. The following year we decided to make this program official by acquiring funding from the cultural ministry as well as other entities and individuals, while maintaining our creative independence in terms of methodologies, objectives, and research interests.

MF: In Colombia, art that engages with marginalized communities has been a source of controversy since Carlos Mayolo and Luis Ospina’s scathing critique of the explosion of exploitative documentary filmmaking in the 1970s, which they referred to as pornomiseria or “poverty porn” (the Spanish term is used widely in contemporary art discussions in Colombia). How do you negotiate the ethical issues that inevitably arise when working with such communities? Is the Escuela an art project or is it simply remunerated social work that allows the collective to sustain its other activities?

HP: The Escuela questions the idea of community as an entity that is external to us as artists and that we must somehow assist in order for it to achieve well-being. This is precisely the problematic, patronizing attitude of those recent artistic practices that one might label as examples of pornomiseria. For us, the community does not represent some distant other or naïve peer—like a younger sibling who we feel compelled to guide with our wisdom. No, we are very much a part of this community as it shapes our environment and the space of our everyday material reality, and for this reason, it is impossible to distance ourselves in this way. We are not privileged individuals sheltered by a sense of comfort that allows us to look the other way. Class tensions in Colombia are evident in these typical accusations of exploitation when one chooses to work with someone in a vulnerable position as if the solution is simply to look the other way in order to abstain from making pornomiseria.

Sometimes it seems that being an artist implies freedom from geographical, economic, or social hierarchies, as if we, as artists, all enjoy the same opportunities, and that because of this tacit agreement “between artists” we must refrain from acknowledging and condemning the landscape of exploitation and inequality that exists in Colombia.

Cultural production in Colombia, then, must always carry the weight of this class tension, so that the school attempts to initiate a dialogue with its participants not from a privileged position but from that of artists who share this complicated reality. While we utilize the structure of the workshop as a point of departure to share and articulate diverse experiences, we also desire to move beyond fixed, conventional structures and methodologies that are often too limiting given the difficult realities we confront.

The school is practically invisible, as it is not exhibited as artwork, although it does address and question codes of representation, communication, and culture. While it comprises an activity that takes place at a specific time, the event and its documentation become a productive memory that continues to inform the future activities and decisions of the school’s participants. To some extent, the Escuela resuscitates the concept of incursion that emerged in the 1970s in Colombia.

MF: Which projects do you think were particularly successful?

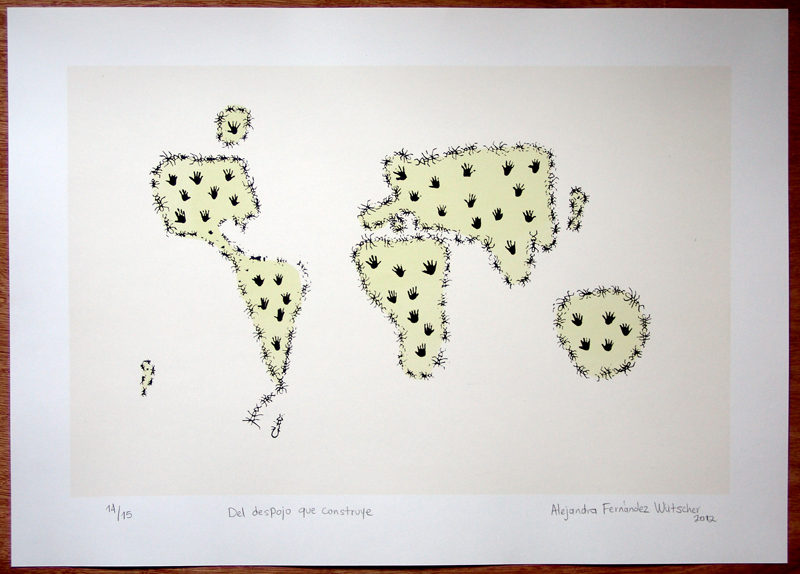

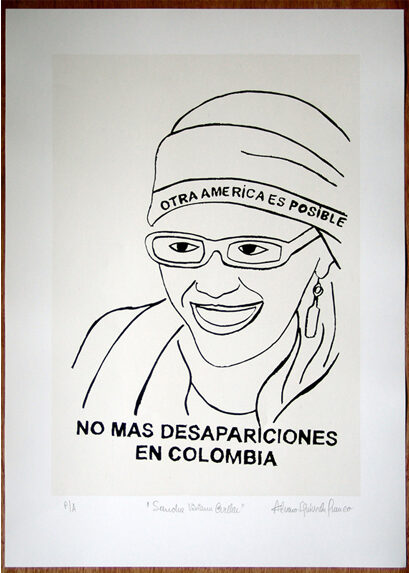

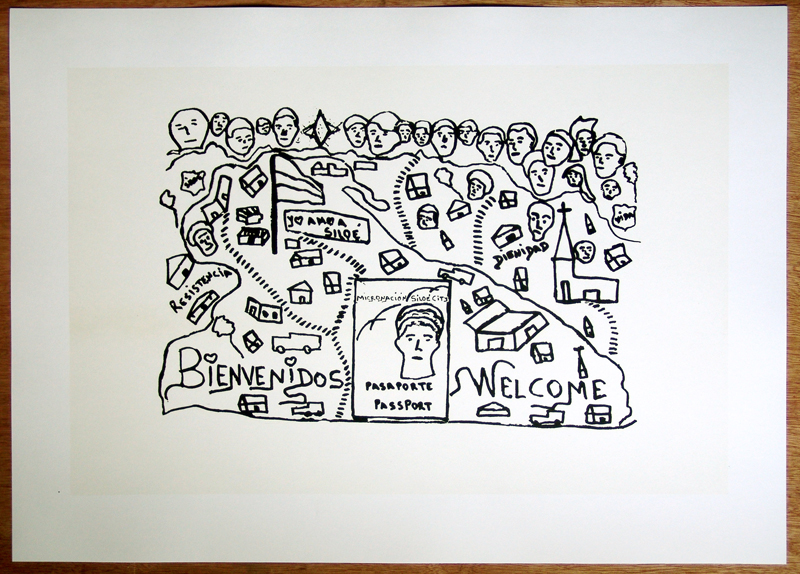

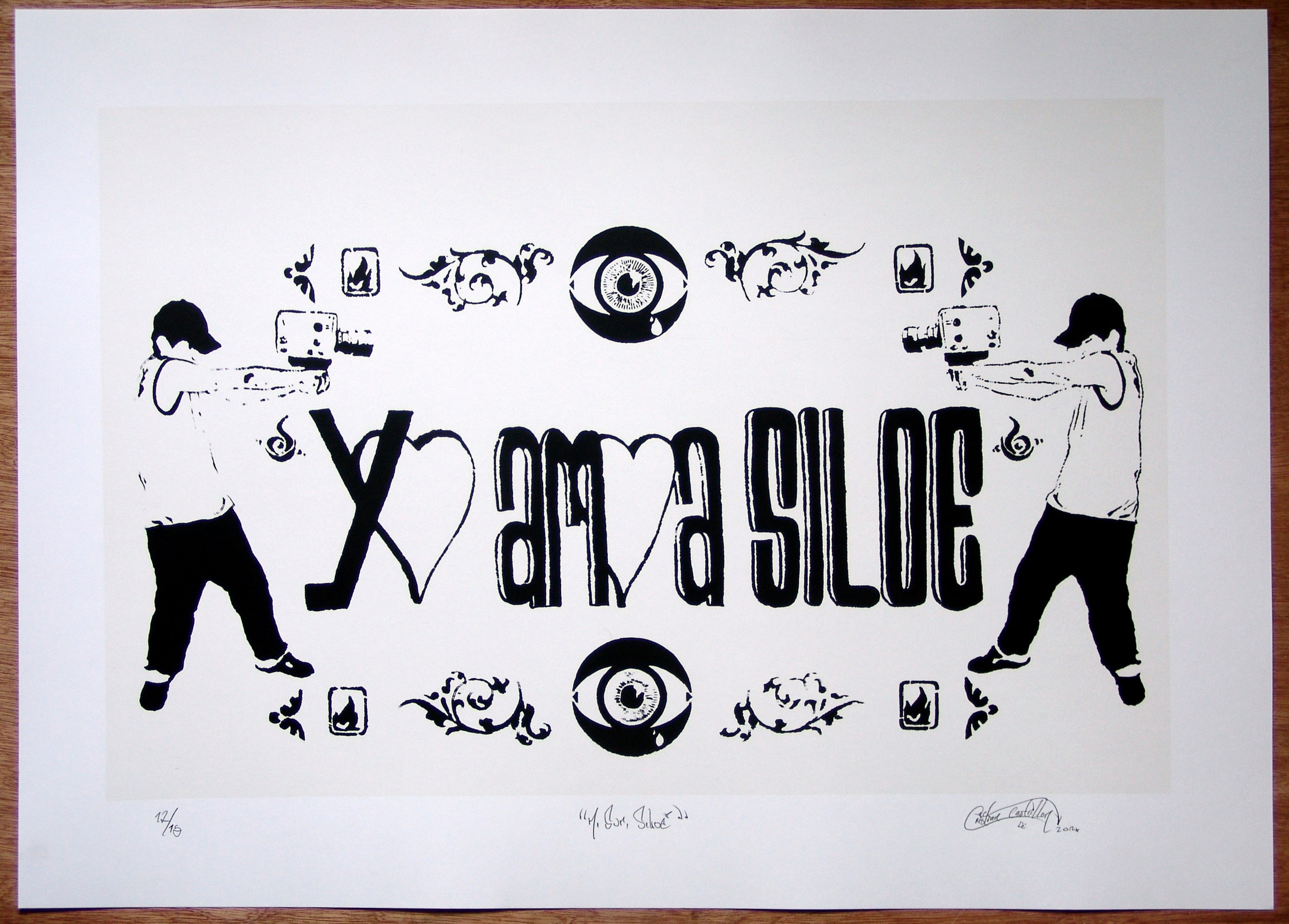

HP: The most recent project enacted by the school, the pedagogical program for the Festival de Performance de Cali VIII, was an important experience. On this occasion, we explored the relationship between theater as a political platform and social movements and forms of representation and presentation. We worked directly with historical actors including academics, artists, union leaders, and members, suffragists, feminists, and representatives of ethnic minorities and human rights organizations. Events included a talk by a theater professor who participated in the student movement in Cali in the 1960s. He spoke about the kinds of theatrical strategies used by student agitators that were subsequently erased by history. Additionally, a member of a historical printmaking workshop in Cali lead a workshop about the posters produced in that era. Venues for these events included union offices, institutional and popular museums, crime-ridden neighborhoods, artist workshops, and the headquarters of organizations devoted to social justice and minority rights. Participants attended the Festival talks delivered by speakers interested in the historical context of the cultural and artistic scene that emerged from the discontent following the military dictatorship of General Rojas Pinilla (1953–57).

MF: Are there any projects or events that you think failed in some way?

HP: Constructing a working method for the school has been a long process. Initially, given that we are artists, we desired to make objects in accordance with the funding guidelines of the cultural ministry. However, over time we realized that this contradicted what we were trying to achieve, and so we moved toward conversational formats that facilitated the possibility of experimentation.

We do not believe any of these experiments have failed. Although the objectives of the initial projects are different from those of more recent ones, they initiated a necessary process that would allow the Escuela to evolve into what it has become today.

MF: What have been the long-term consequences of the Escuela’s activities from the participants’ point of view?

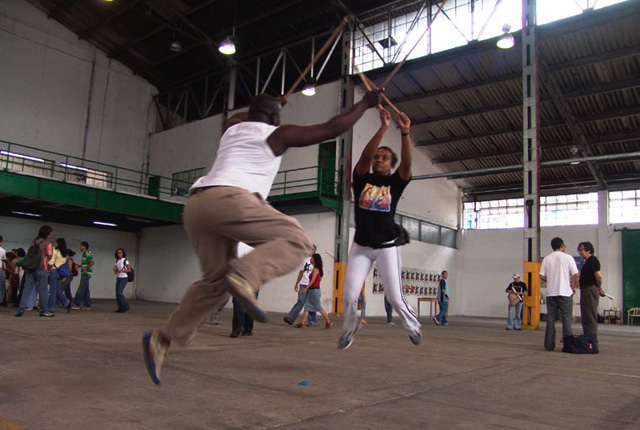

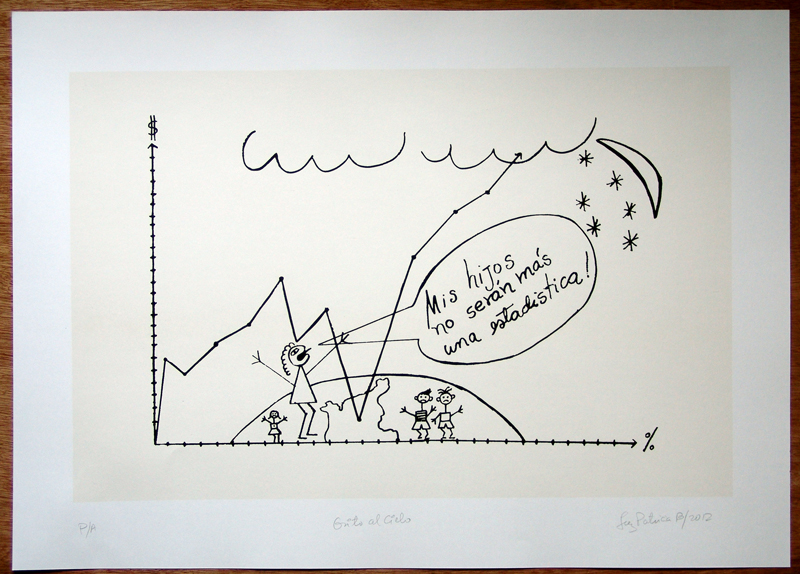

HP: The results of the processes facilitated by the Escuela belong to its participants, so we only know what people tell us. The dynamic of the school motivates participants to continue initiated activities even after the school has adjourned, as was the case, for example, of the school of fencing with a machete in Puerto Tejada. The original objective of the school was to provide a historical context for this fencing tradition but it soon became clear that the creation of a foundation was needed in order to reconstruct this very history. In Juanchaco and Ladrilleros participants were also interested in reconstructing their own history through the recollection of individual memories. In this way, they actively collaborated in the publication produced by the Escuela, along with an educational project about this place.

In general, the participating groups make their own decisions without our intervention. We simply facilitate the development of self-organized platforms that provide continuity for the groups, the friendships established, and organized activities, and from there they themselves decide if they want to further interact with us or not.

MF: Have you implemented any sort of methodology to measure the outcomes of the Escuela’s activities?

HP: We have not implemented any such system because we are more interested in initiating dialogues in order to reconstruct these forgotten historical narratives. We might say that the results are evident in that the Escuela has continued to exist because we continue to receive invitations and because are talking about it right now.