I remember the first work that I saw of the Isuma collective, it was a video released in 1993 called Saputi (Fish Traps). Like most of Isuma’s videos, the emphasis is on action not on dialogue. The camera follows a family in the late fall as they go about setting rock traps along the shallow water near the shoreline to catch fish. It’s a sustainable practice based on knowledge of the tidal systems and fish habitat that goes back hundreds of years—when the tide goes out and the water recedes larger fish are trapped in the rocks, making for easy catch for the family. The film doesn’t build up to a big event rather, it is made up of the culmination of small moments; a hand comes in to help another move a stone, small talk shared as people slowly tread across the tundra toward the open water, the time spent in silence waiting for a catch.

From the beginning, Isuma’s practice was different—they were the only video-makers active in this part of the Canadian Arctic. The word Isuma in Inuktitut roughly translates as “thinking for oneself,” self-definition and determinism that is rare in this part of the world. Zacharias Kunuk, one of the co-founders of Isuma Productions, had his start at the Inuit Broadcasting Corporation just a few years after he bought his first camera. In 1984 there was still little content broadcasted in his community that originated in the north. In fact, Igloolik was one of the last Arctic settlements to get TV. They kept voting it out because of lack of northern content. In a recent conversation Kunuk relayed how he felt that the programming then was also conservative, it was very difficult to speak about any issues facing the north and certainly not politics. He took things into his own hands, quite literally, in 1981 when he sold some of his stone carvings to a gallery to buy his first Sony Portapak video camera. He was interested in video because of a shift he had observed in his community. The youth, who in the past had learned cultural knowledge through Elders’ stories, was no longer listening. Instead, they were gathering in front of TV sets. Broadcast television had come to replace oral tradition. Instead of being a detriment, he saw it as an opportunity and one that he didn’t want to take on alone.

Individual pursuits don’t make a lot of sense in the Arctic. Collectivity is essential to survival. You would never hunt alone lest you get injured or captured in a blizzard. Walrus can weigh more than 1000 pounds, catching a seal is a waiting game at air holes, to harpoon a whale can take dozens. Caribou also requires intimate knowledge of migration patterns and a means to not only track an animal but to find your way back in a flat treeless environment. Families are tight-knit—it wasn’t that long ago that everyone lived in the same room and shared a common bed to stay warm over the long winters. Kunuk soon began working together with his collaborators. In particular, experimental videographer Norman Cohn had relocated from Montreal, Quebec to Igloolik. Together they would change the face of Canadian filmmaking practice, first with releases like Nunavut (Our Land), a 13-part mini-series made particularly for the television format, and later the renowned feature-film Atanarjuat: The Fast Runner. It was only when Atanarjuat started to receive awards overseas, including the Caméra d’Or in Cannes, that they started gaining more recognition back in their home country as well.

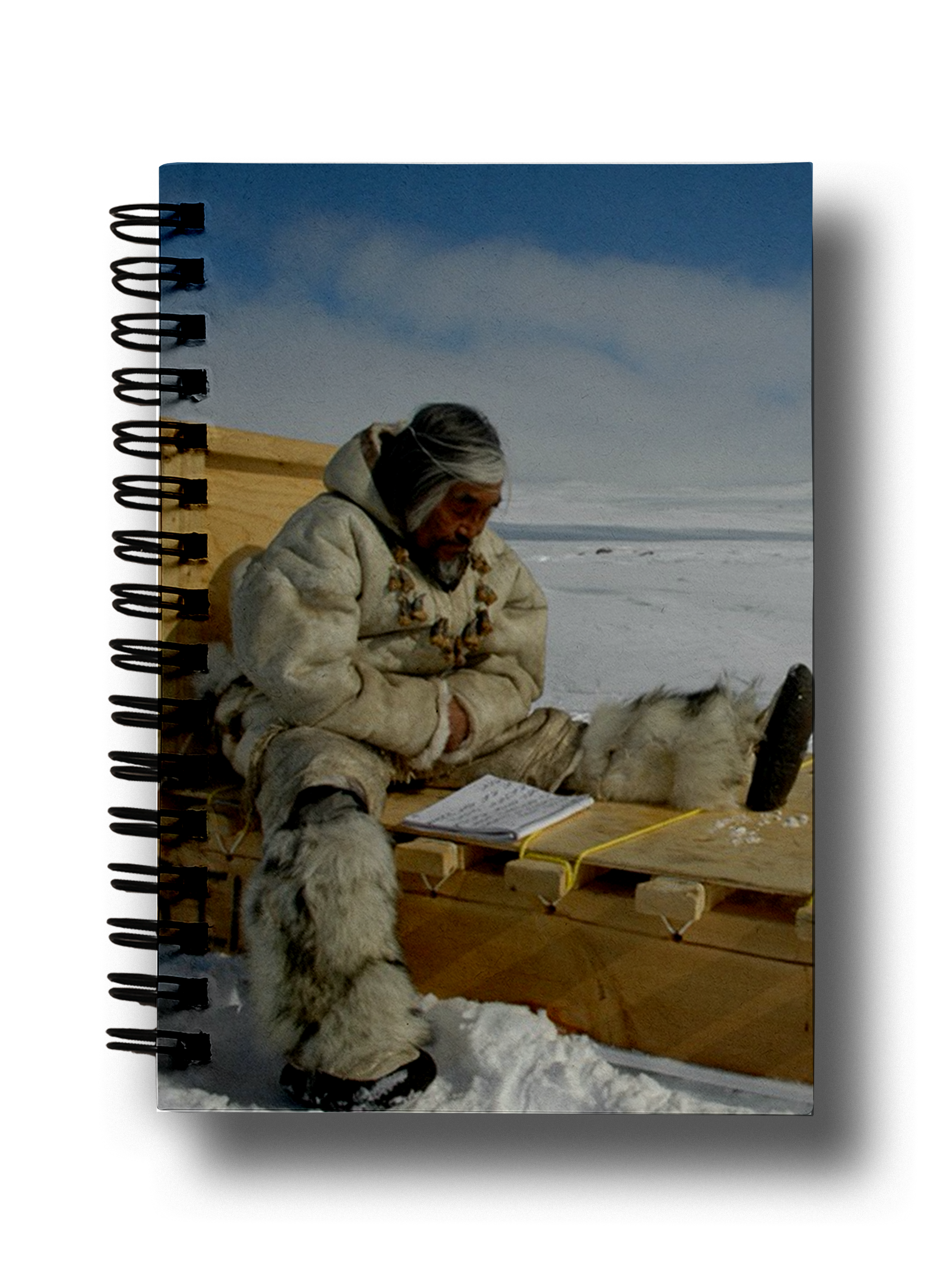

This collective methodology extended to the production process. In Igloolik, there were no trained scenographers, costume designers, audio technicians or actors. Instead, seamstresses, predominantly elder women, sewed costumes and in the process passed on vital traditional knowledge, including how to make waterproof stitches in sealskin boots; others were engaged in making igloos, hitching sled dogs, and making harpoons for hunting. At the same time that they were acting these customs, others were learning these skills. This is how culture stays alive. Isuma simultaneously produced a cultural investment and an economic one which is unique. Most of the artistic production from the north is immediately sent south, including thousands of stone sculptures, prints, and drawings each year. Art is one of the largest economies in the north and more people identify as artists here than anywhere else in Canada. In the 1940s and 1950s art came to fill in the void left by the collapse of the fur trade at a time when Western economic models were replacing sustenance lifestyles and modest trade. For Isuma, film production is a means to provide well-being in the broader community and is a way to provide for the well-being of the community.

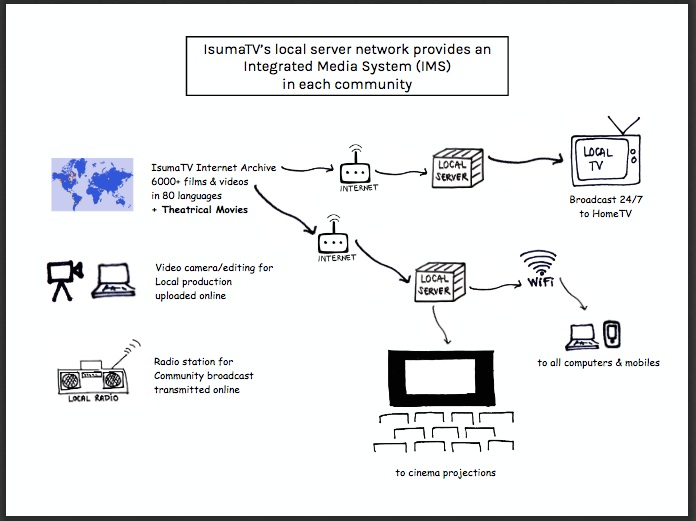

This idea of community-driven accessibility and an expanded idea of wealth are also at the center of IsumaTV. Initiated in 2008, IsumaTV is a web platform for Indigenous videographers and filmmakers to share, stream and discuss content. Its content is deliberately broad including experimental shorts, animation, documentaries, and dramas, and connects Indigenous media makers from around the world. Multi-lingual and multi-vocal, it now includes content in more than 80 Indigenous languages. Instead of focusing on publishing long texts, the platform is indebted to oral languages, making deliberate use of symbols and color coding in place of long narratives.

Yet a major challenge in remote indigenous communities remains digital access. Broadband in the Arctic is slow and the cost prohibitive for most individuals, meaning that the Internet is often shared communally among families or accessed through institutions such as schools. Recognizing this as a barrier, Isuma has installed media players in Indigenous communities across the Arctic and in Haida Gwaii. Through these media players, they have created a new form of digital TV. The players are loaded with all of the Isuma content internationally, which is then streamed for free on one of the local TV channels. For them, this is a part of the process of democratizing new media. They write that:

New Media democratization allows new groups of people to access media tools that were initially exclusive to them. People can use media to recover language and indigenous traditional strengths and transform these into contemporary strengths. IsumaTV is available to anyone with an Internet connection and a computer or mobile device.

Digital media access often falls along social strata, cutting the poorest communities out of the network. In Canada, Indigenous communities are often described as being the third world suspended within the first world. Multiple families often share single houses because of chronic shortages, youth suicide is now at epidemic proportions, and opportunities for non-traditional education and employment are also challenging. IsumaTV is making a difference by giving Indigenous media-makers a voice, through this they are also gaining agency and an audience.