In 1972, the Australian government denied rights for land to indigenous people while granting access to mining and land properties to the crown. As a response to these events, the Aboriginal Tent Embassy was settled in the capital city of Canberra, just in front of the parliament house. It was from this position, that activists and supporters that arrived from all over the country claimed for justice.

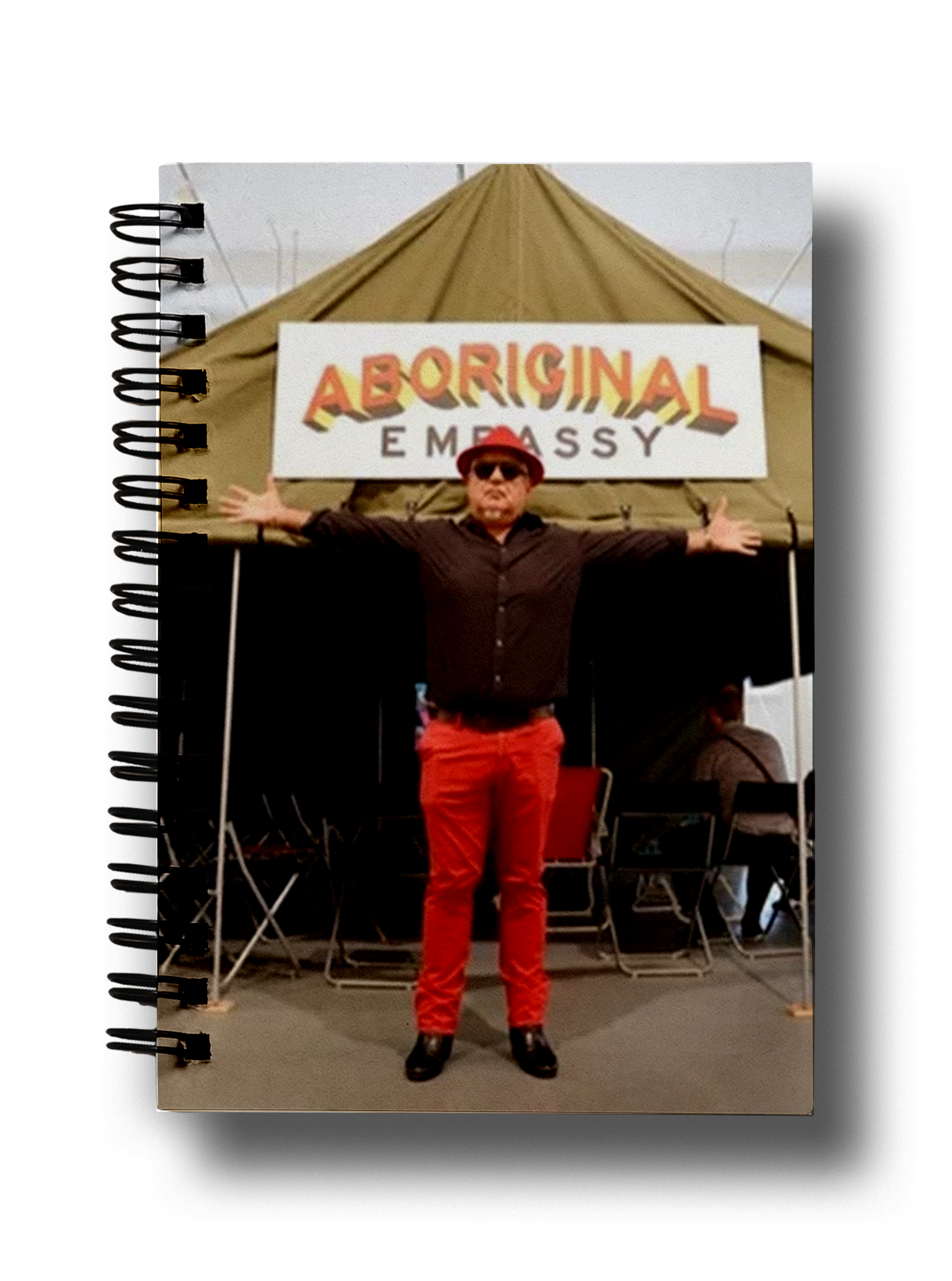

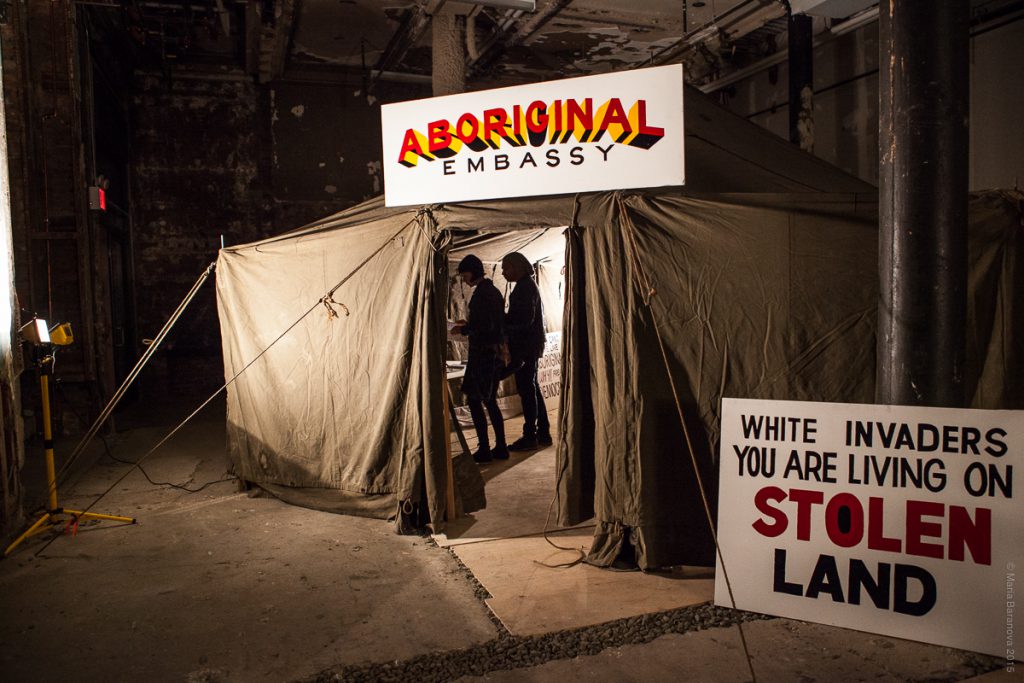

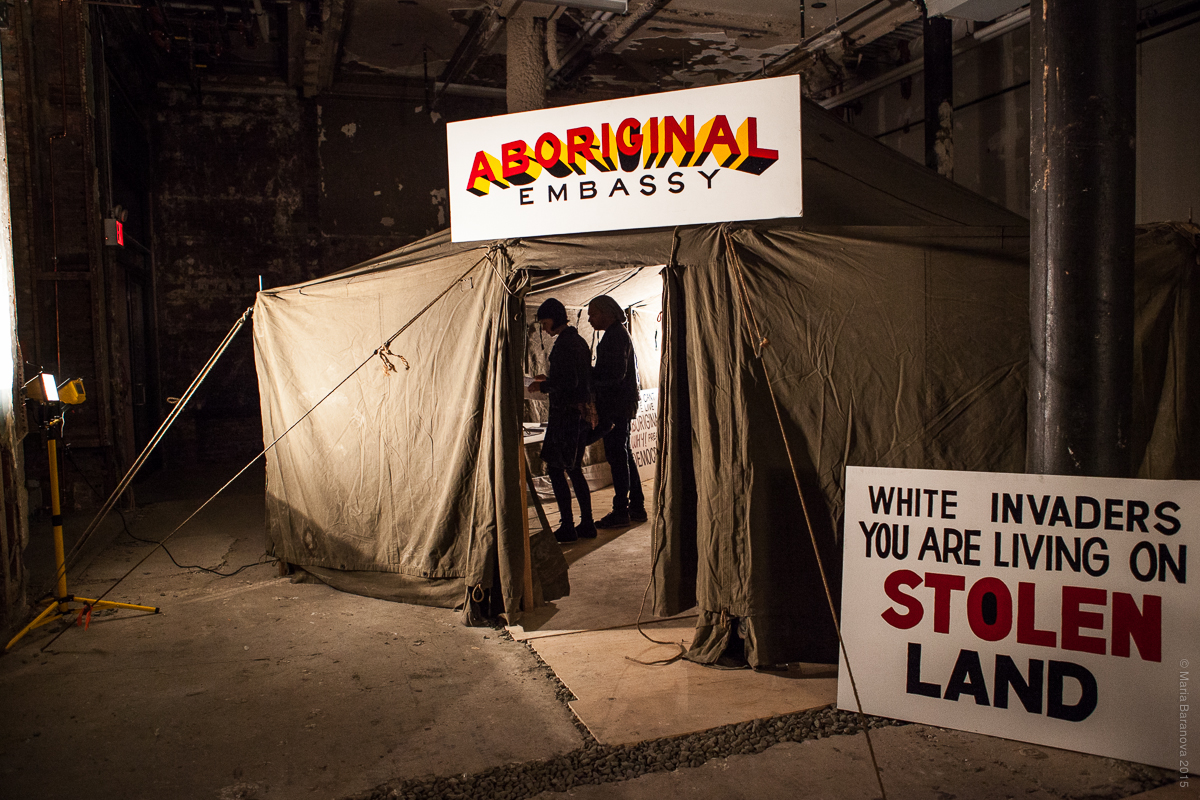

Richard Bell wasn’t in Canberra when these events took place, in fact he was a kid. But it has been later when he got to know some of the activists that were part of the occupation in 1972, that he became politicized. Now, having developed a great connection with them and with their struggles, he has come to define the first Aboriginal Tent Embassy as the greatest work of performance art. In fact, some theatrical and artistic aspects have always defined the image of the movement, such as the design of the aboriginal flag or the tent architecture. By initiating the project ‘Embassy’ Bell has had the opportunity to further developed this idea. Since 2013, he has brought Embassy to different parts of the world, aiming to create a dialogical space that has been neglected for long time. Embassy transforms and adapts to each context, although there are some elements that always remain the same as a homage to the original one. One of them is a beach-umbrella, a replica of the original Tent Embassy around which activists protested in 1972. Another one is the tent, which includes slogans and the well known ‘aboriginal embassy’ sign.

The core basis of Embassy is to generate a space for gathering and debate, where it is possible to assert the rights of aboriginal people. The project wants to ensure that aboriginal history is not dismissed anymore by the Australian state, and it does so by speaking of these issues to the world at large. Its projection into other realms, through the platform of contemporary art, aims to create a change for oppressed people globally. Furthermore, it represents an attempt to use art as a socio-political tool, from which activists and people fighting for human rights can benefit.

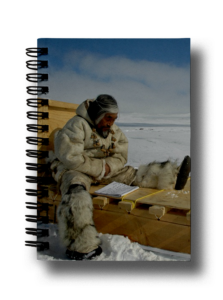

Embassy’s appearance is very peculiar. It takes the shape of a tent that is transported or reenacted in different places. This nomadic-architecture and other theatrical aspects that surround it have, on some occasions, been considered as one of the strengths of the project. In fact, these characteristics were also present during the occupation of 1972, when artists and members of Black Theatre movement participated not only with their presence, but also with their work. Additionally, Embassy can be quickly unmounted and re-erected in different places. A capacity that made it so easy to evict in 1972, but which also allows it to be reborn in new locations. Now, Bell thinks about this new traveling Embassy, that is active since 2013, as a satellite of the original one.

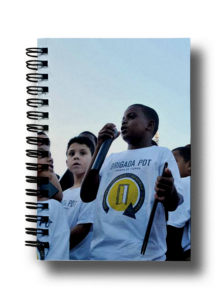

It is also important to highlight that Embassy does not only claim for rights of aboriginal people in Australia. Even if the project takes as a point of departure the events of Canberra, it also addresses the struggles of racialized and indigenous people in other parts of the world. In each new context a network of friends helps to establish connections with local groups and activists. By doing so, Embassy unites forces with other people and their stories, and develops mutually supportive networks. They gather in the open and public space that Embassy constitutes and gives visibility to their dismissed history. For example in New York, activists from Black Lives Matter, the Black Panthers and the Idle No More movement got together to give lectures, screen films and discuss issues in a spirit of solidarity.

The work of Richard Bell is most of the time operating in parallel to the objectives of the Embassy. He uses art as a political tool and it is his focus to overcome terms such as ‘Aboriginal Art’. An expression that, he argues, is the product of colonial attitudes that are still intrinsic to Western Art. These kinds of labels and behaviours relegate art of aboriginal people to a lower position. Paradoxically, it is mostly white-people who become the visible ‘experts’ of aboriginal art while aboriginal artists are dehumanized and excluded from the system that western society has created to legitimize itself, its culture, and its continuing exploitation.

As Bell says, post-colonial regimes have to a great degree equalled or surpassed the paternalistic and feudal attitudes of old colonial regimes. For example, one of the arguments of the Australian government is to assert that today aboriginal people have no rights – they have privileges. Which (ironically) seems to imply that white people are in an underprivileged position. That these dominant and racist attitudes are still present in Australia and further in the world is what makes out of Embassy an extremely urgent and necessary project. Even if departing from the small space of a tent, Embassy manages to use art to further the outreach of claims and stories shared among its participants. It is exactly what a public space should be, open and horizontal, giving voice and presence to all those who are silenced and whose rights are neglected.

Richard Bell’s aim is to keep bringing Embassy to other parts of the world. Among other things, he will present it this year at Tate Modern in London. But most importantly, he will also try to establish new connections with neighbouring places like Indonesia, the struggles of which share many similarities with those of aboriginal people in Australia.

List of sources:

Bell, Richard. Bell’s Theorem. e-flux (online) Journal #90, 2018.

Gilad, Lio and Folgado. Interview with Richard Bell and Josh Milani. October, 2019.

Howell, Foley and Schaap. The Aboriginal Tent Embassy: Sovereignty, Black Power, Land Rights and the State. New York: Routledge, 2014.

Tan, Monica. The Aboriginal Tent Embassy: ‘We were all young, crazy, but we believed in justice’. United Kingdom: The Guardian (online), 2016.