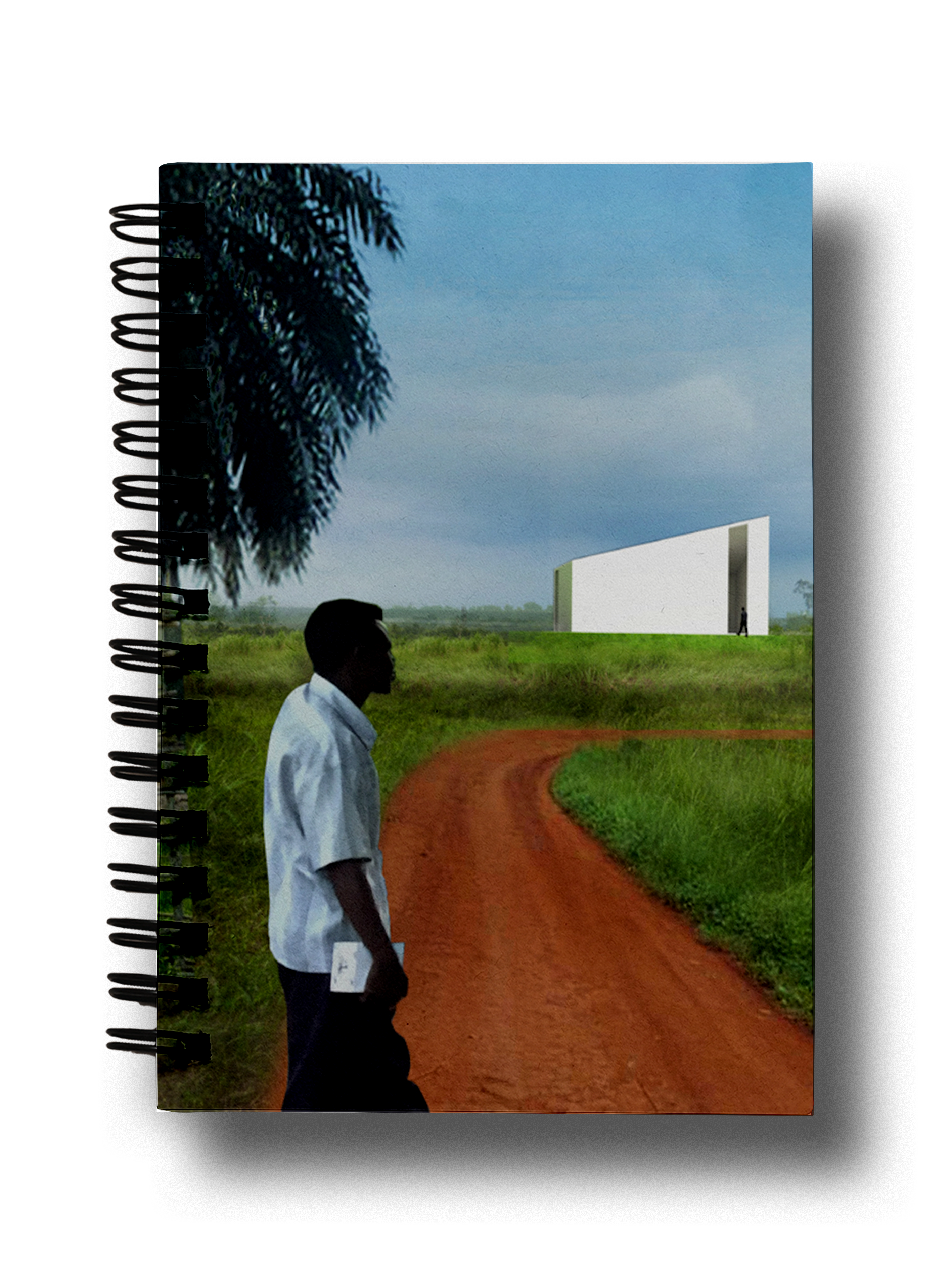

On April 21–22 2017, a White Cube opened on the site of Unilever’s first ever palm oil plantation in Lusanga in the D.R. Congo, 650 km southeast of Kinshasa. Designed by OMA, this White Cube is the cornerstone of the Lusanga International Research Centre for Art and Economic Inequality (LIRCAEI). Next to the inaugural show curated by the plantation workers’ cooperative CATPC, the opening weekend included a film programme, discussions on the plantation system and its ties with the art world, and an exchange over skype between plantation workers from Congo and Indonesia. The event was organised by the CATPC and its sister organisation Institute for Human Activities (IHA), that facilitates the dissemination of CATPC’s activities.

It was in the framework of this opening weekend that Suhail Malik (Goldsmiths, University of London) travelled to Lusanga to give a talk on the value chain of art, the function of a White Cube on a global scale, and the possibility to reverse the extractive mechanisms ruining the Global South. A few months after this event, IHA’s research coordinator Nicolas Jolly and its artistic director Renzo Martens debriefed with Suhail Malik.

Nicolas Jolly: So, first a mundane point, tell us all about the difficulties you had with getting your visa for your visit to Lusanga.

Suhail Malik: Sure. It normally takes a quite a while to get a visa from the Congolese Embassy in the UK and we had to do it in a week.

NJ: Well, it’s usually difficult for Congolese to get into Europe, not for Britons to get into Congo.

SM: Maybe, but there were people at the embassy who had come back after waiting more than eight months for a visa because they needed their passport back to travel elsewhere. So they had to cancel the whole application process… A lesson to be drawn from the visa situation is that if your project wasn’t plugged into some art establishment and people with influence on the Ministries within the Congo, we just wouldn’t have gotten anywhere at all.

Renzo Martens: More often than not, people don’t want to get involved with power relations in art.

arrow_upward

arrow_upward

arrow_upward

arrow_upward

SM: I think it’s stronger than “don’t want to get involved”. I think people repudiate power, as corruption of the ethical truth of art’s critical moment. And I think what your project does is to try and use power structures to effect the changes that have been declared by it.

Your project sets up an engagement across a global hierarchy, which stratifies places of high reputation and places like Lusanga, which is not even marginalised but rather altogether absent from the map. You’ve connected this previously absent point to the centres of power in the art world. But also there’s a kind of hierarchy within the Congolese art scene, and you produced a kind of restratification within that scene as well. You produce stratifications and hierarchies in a new way.

RM: Do you think that LIRCAEI is relevant within a post-colonial framework? Does that interest you at all? Because in that field one often tries to deny the White Cube its agency, or one blames it because obviously, the White Cube is an apparatus of power.

SM: What I see happening with your project is something much more about current forms of economic and social modernity, where it’s no longer comprised or dominated by a colonial relationship. It’s a modernity formed in part by economic extractions, which are exploitative, but these exploitations are also happening from within the South, as well as from North-South. There’s a reconfiguration of what the extracted relationship is different from colonialism or even imperialism. The anthropologist Aihwa Ong talks about something similar happening in East Asia, where a new type of globalised South modernity is being constructed by global chains, some of which are de-territorialised, some of which are territorialised. Such constructions seem to be the kind of complex formation that you’re working with. So for me, to describe your project in terms of post-colonial tropes is too limited a logic. Where you’re actually operating is in the more complex formation of the global economy, the global culture that is being set up now.

NJ: Now that you’ve been on site, would you change anything to the affirmative talk you did?

SM: I don’t disavow my engagement with the project. I think there’s a lot more to be done with it. One of the tasks ahead is how you coordinate what you do with it, in terms of its manifestation in the global art field and also with regard to how it reorganises the Congolese art space. Because if it’s successful, it’s going to have major effects. And then the other immediate effects are what it does within the Lusanga village, the former plantation. That will be the moral test of your project because the consequences are existential. I think if the White Cube is just a place in which this relationship between the rich North and the very poor South gets played out, or gets demonstrated, and that’s a smart move in essence for the art system, that’s already doing something, but in a way it is only doing something for us who are anyway the beneficiaries of the global system of extraction from that place and others like it.

RM: It wouldn’t be enough.

SM: Not if your project is a moral project, right?

RM: Sure. The end goal has been clearly identified by the Cercle d’Art des Travailleurs de Plantation Congolaise (CATPC), with their president René Ngongo. Whatever type of capital that is being attracted from the art world to Lusanga is reinvested into starting a new type of plantation in their own hands, owned by them, what we call “the post-plantation”.

SM: I think what your project demonstrates is the way in which those moral compunctions don’t have to stay at the level of just witnessing immoral things elsewhere, and getting a kind of kick out what you witness. That’s common enough in contemporary art — sliding into documentary photography. In intervening and trying to rectify them, you’re actually trying to transform an area which is destitute into something less bad.

RM: And simply through using the apparatus of art….

SM: In a way, your White Cube functions in a regular pattern. That model is gentrification, in which a White Cube is a sort of leading edge of new investments. But the very rapid and improper use of the White Cube through your project means that you have bypassed the whole “Let’s wait for a certain point of development and then move in on it”, typical of gentrification strategies. The Lusanga White Cube certainly speaks to an art world that often claims to be interested in the same issues of global poverty, but not in the usual art way of dealing with it, which is to shine a light on something, whereas your project is a very clear and strong intervention. Because what you do here is to move directly in Lusanga to reorganise that village. There you don’t have to deal with the usual art world politesse, so your intervention is more directly social and not just artistic. It’s a very new thing, so the consequences still need to be understood.

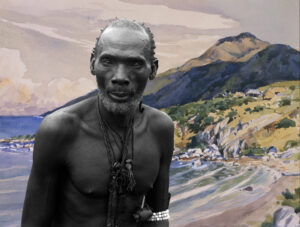

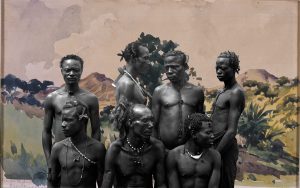

NJ: We’ve touched on the White Cube, its value chain, and its moral economy, but now I want to hear your opinion on CATPC.

SM: I was impressed with the Skype session between the CATPC and the Indonesian plantation workers’ union SERBUNDU. What struck me was what had been set up there between the plantation workers in the Congo and those in Indonesia, in the sense that actually we need to talk to one another, to think about global plantation workers’ conditions and how they compare — and also the relief on the Congolese side that they get paid much more!

I also didn’t know that plantations are still primary in world systems. They’re not just historical relics or marginal to global economies. So the second lesson was that the move being made by CATCP was to reformulate the plantation. They seem to be saying: “our economy will continue to be a plantation economy because that’s what we can do, but we need to rethink it”. My anticipated sense would be that they would want to abandon the plantation and think about setting up some kind of high-end, rapid development site of growth, like a construction factory for computer chips (as an extreme example). But actually, they were saying “no, we can think about plantations in another way”. That was very instructive and very powerful.