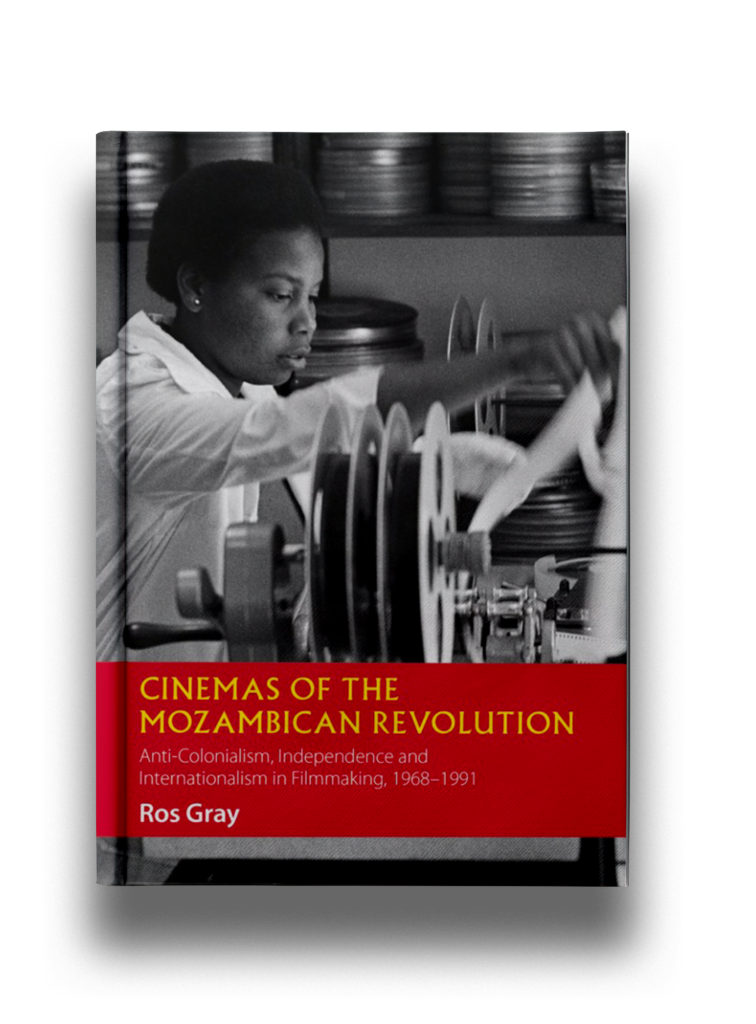

Year

2020

Publisher

Boydell and Brewer

Author

Ros Gray

Annotation

In Azoulay’s Potential History, key moments across time and space that had previously for the large part been overlooked are taken as potentialities that demand to be attended to through the mode of ‘rehearsal’. In some senses, Ros Gray’s Cinemas of the Mozambican Revolution makes a similar move, albeit through a different vocabulary. As with Garland Mahler’s caveat of not wishing for a wholesale retrieval of the Tricontinental in a triumphalist and romanticised embrace, Gray’s book is far from a mere idealization of the period and is attentive to the frictions and contradictions therein, especially where the films in question’s afterlives are concerned. But the main thrust of her reading is one of the revolutionary potential of the cinemas of the period.

In 1976, Frelimo (Frente de Libertação de Moçambique, the ‘Mozambique Liberation Front’), which had led the armed struggle for independence against Portuguese colonial rule and had in 1975 formed a government, set up the Instituto Nacional de Cinema (‘National Institute of Cinema’, INC). The intention was that a new generation of Mozambicans ‘should be trained up as part of a wide-reaching revolutionary project of decolonisation that was intended to destroy the injustices and hierarchies established through colonial rule’ (p. 1). With equipment gifted by the Soviet Union, cinema, so the idea went, was ‘the conduit and embodiment of socialist friendship and an agent of political change’ (pp. 1–2). Through close readings of select (often extremely rare) films, together with narratives of production and its context compiled through numerous interviews carried out over more than a decade with key actors and archival research, the book is a fascinating account of a period of experimentation with regards to the social and political role of filmmaking. Beginning with Frelimo’s initial experiments with filmmaking as part of the armed struggle for independence (the first film being made in 1968), the book ends in 1991 with a fire in the INC’s archive and the privatisation of the film industry as Mozambique began the transition from a Marxist–Leninist command economy to the free market and multi-party democracy, following the collapse of state socialism in the late 1980s. Just as Bajorek’s reading of West African photography (see below) goes against the grain of standard academic classificatory systems, Gray’s framing of her reading through Frelimo’s revolutionary politics of this radical moment of internationalism and decolonisation allows her to sidestep the categories of ‘national cinemas’ and ‘world cinema’ that often structure contemporary film studies and that ‘have become naturalised but in fact emerged in particular conditions of the restoration of capitalism through the neoliberal order’ (p. 264). Instead, Gray demonstrates how Mozambican cinema of the period was a site from which African decolonisation made a planetary call for revolution to destroy imperialism at the same time as developing a vernacular form of cinematic expression in pursuit of national unity.

Returning to the notion of potential history, Gray’s framing device for the period in question is that of the ‘radical moment’, which she borrows from the Marxist sociologist Henri Lefebvre: ‘It is not a linear measurement of duration but rather the radical moment reveals new possibilities that break through the barriers that limit emancipation. While it signifies a rupture, the radical moment also animates the dual meanings at play in the word “revolution”, which means both a break with the past and a cosmic cycle, and is, in Rob Shield’s words, “full of anticipation, insights into the future and déjà vu’’’ (p. 4). Gray continues: ‘In resisting the trope of disappointment that tends to cast revolutionary change as doomed to failure, this book retrieves the notion of the radical moment to understand the continuing affective charge of these films that anticipate a new society, even while fraught with the contradictions of the past and enduring forms of injustice’ (p. 12). In terms of that which endures, albeit in modified forms, Gray employs the term ‘afterlives’ in the sense given to it by Kristen Ross, who reads historical events (for instance, May 68 and the Paris Commune) against the grain of dominant retrospective interpretations, often emphasising the overlooked anti-colonial and internationalist impulses therein, and, as per Gray’s approach, engaging with the perspectives of key actors, ‘who understood that they were involved in moments of significance in the human history of the world’ (p. 13, n. 11). Jumping forward to the more recent past, the concluding chapter offers insight into the re-emergence of some of the films examined in recent years. Examining the effects of the cinemas of the Mozambican Revolution through this sense of afterlives means addressing them as part and parcel of the social memory that surrounds them, as cultural texts that on the one hand ‘still carry the potential to de-naturalise dominant narratives about the conditions of the present’ but on the other hand, as per any mode of cultural production, are ripe for being harnessed or appropriated in order to maintain the status quo of the present. In a moment in which calls for ‘decolonisation’ can be heard throughout the cultural industries, Gray demonstrates the proleptic nature of this period in which the INC ‘developed a successful self-sustaining system of acquisition and distribution that funded production’ and the book ‘situates film aesthetics within the wider context of production, distribution and exhibition that was part of an attempt to decolonise the film industry within Mozambique and in alliance with other decolonising countries’ (p. 5).

Shela Sheikh

Cinemas of the Mozambican Revolution: Anti-colonialism, Independence and Internationalism in Filmmaking, 1968–1991 is motivated by the desire to understand what was singular about the experiment with the moving image that began in Mozambique during the armed struggle for independence, when foreign filmmakers were invited to make films that would break what Eduardo Mondlane, first President of Frelimo, called the 'curtain of silence' that hid the reality of Portuguese colonialism from the rest of the world. The book argues that during the Mozambican Revolution a political aspiration animated moving image production that sought to harness the collective experience of cinema for the purposes of radical social transformation and decolonisation. Cinemas of the Mozambican Revolution frames this history and analysis in relation to the revolutionary politics of that moment, examining the new cinematic forms that emerged in dialogue both with vernacular culture and local imperatives, and with wider internationalist trajectories of militant filmmaking.